You are reading a DM Rare Coins Original Research Article. Find More!

Posted 8/25/17

Distinguishing Dickeson's Dollars:

1876 Dickeson Continental Currency Dollar Imposters

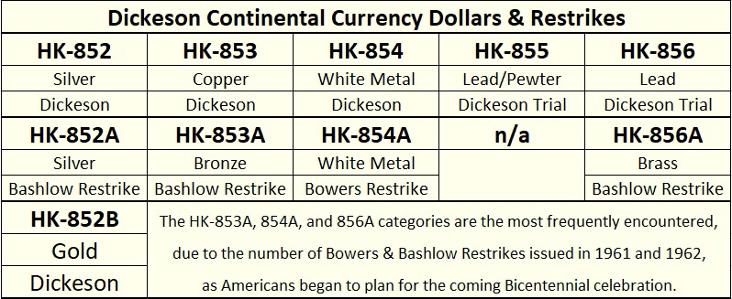

The Dickeson Continental Currency Dollar Copy of 1876 is such a perennial favorite among Hibler-Kappen, So-Called Dollar collectors, that it even has its own restrikes.[i] After all, these medals are the closest most will ever come to owning the prohibitively expensive, 1776 Continental Currency Dollars, upon which they are based. The original Continental Dollars were primarily struck in pewter, with just a few in brass and silver; and were likely produced between 1776 and 1783.[ii] New research suggests these pieces may have actually been medals, not coins. Value-wise, they start out around $20,000 in the worst condition. However, the Dickeson version of 1876, and its various 20th Century restrikes, which come in similar compositions, are much more affordable by comparison. They start at about $1000 for the 1876 and about $100 for a modern version. That said; the 1876 medals, and particularly those struck in copper, cataloged as HK-853, are actually scarcer than some of the 1776 pieces. So elusive is an authentic HK-853 that few people have seen one, and its modern restrikes are often mistaken for the real thing. Collectors, dealers, auctioneers, and even some expert graders have been fooled by common 1962 bronze restrikes, masquerading as rare 1876 copper originals, due to the lack of accurate, published information on the differences between them; until now.

During the 1876 US Centennial Convention in Philadelphia, Montroville W. Dickeson; 1809 to 1882; capped off his long and illustrious career as doctor, archaeologist, numismatist, and author of the groundbreaking, American Numismatic Manual of 1859, by presenting his own version of the famous Continental Currency Dollar.[iii] These medals were minted by the hundreds in gleaming white metal, HK-854, with just a few handfuls struck in showy, red copper, HK-853.[ix] Trial strikes also exist in lead and brass, and a few dozen were struck in silver. Collectors often find the copper version the most aesthetically pleasing, and with an average thickness of about 4mm, they were hefty and substantial works of art. Unfortunately for collectors, the HK-853 is exceedingly difficult to find today.

It should be noted that these Dickeson medals are often incorrectly categorized as “restrikes.” However, Dickeson created a more refined, innovative design than seen on the 1776 Continental Currency Dollar. While mimicking the 1776 issue, his is much more sophisticated in both style and execution; perhaps representing what the original may have looked like had it been coined a century later. Thus, because it is a new design, it is not a restrike, and more appropriately referred to as “the Dickeson Continental Currency Dollar,” or even “the Dickeson Copy,” etc.

Despite the enhancements, Dickeson’s dies maintained a level of rustic craftsmanship, due to a number of delicate, hand-engraved features, such as the wood grain of the table top. The letters were hand punched, and they show numerous re-punched characters, as the engraver struggled with alignment. Many of the original Dickeson Continental Dollars were noticeably double struck, as well. It was not uncommon to strike a medal many times before the full design came up. Also of note is the hand-engraved rim beading. It was probably applied in sections with a punch containing several beads, as there is a raised shelf connecting them. The sections must have been meticulously overlapped, end over end, as a doubled image shows on each of the overlapped beads.

Original 1776 Continental Currency Dollar, Pewter.Images Courtesy of Heritage Auctions

An original 1876 Dickeson Continental Currency Dollar Copy

HK-853, Copper

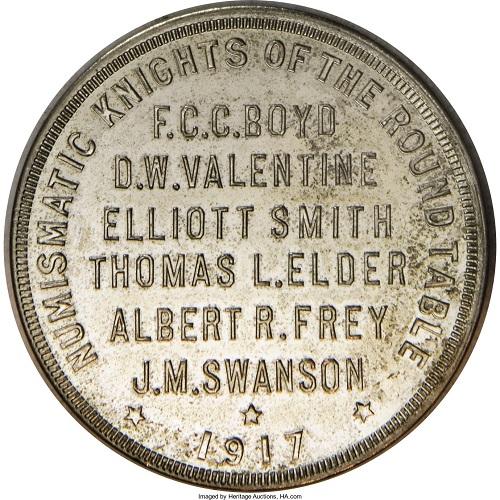

The Dickeson Continental Dollar Copies were coveted medals, even in their day. And, there seems to be some controversy concerning where the dies went, and exactly how they were used, after Dickeson’s death in 1882. Some have suggested that additional HK-853 mintings took place.[v] All we know for certain is that the obverse die was in the possession of Pittsburgh coin dealer and auctioneer, Thomas Elder, in 1917. Where they were located before that is a mystery. Whether or not Elder possessed both dies; and more importantly, whether or not he decided to make any additional HK-853 medals from them, is undocumented. However, there is much that can be learned from the dies themselves.

There is no evidence that Elder made medals using both the obverse and reverse dies. The condition of the obverse die in 1917, when he used it, does not match the condition of the die seen on any of the HK-852 through 856 medals. This suggests he did not use both dies. Additionally,it was believed, for many years, that Elder was responsible for pairing Dickeson’s Continental Dollar obverse die with other reverse designs to strike a new series of medals combining one design with another. This is what numismatists would call a "mule" or a "muling." The first documentation of these new creations came when they were conveniently offered in Elder’s numismatic auctions, in the early 1900s.

However, a study in 1980, by numismatist and Elder specialist, Thomas K. DeLorey, suggests the thick planchets used for these mulings were more similar to the work of Dickeson, “or one of his contemporaries,” than to the documented works of Elder.[vi] DeLorey could not prove they were the work of Dickeson, but he chose to list them “as such only to disassociate them from Elder.”[vii] In other words, Elder did not make them, but Dickeson might not have, either. DeLorey’s general observation was that, “the letter and number punches” for the various mulings were “noticeably 19th century in style,” but also different from those used for Dickeson’s work.[viii]

The Continental Currency/Confederation muling combined Dickeson's obverse with a reverse of unknown origin. HK-860.

Images courtesy of Heritage Auctions.

For example, the lettering on the Continental Confederation muling reverse, HK-860, is clearly of different style than the Continental Currency obverse. Another indication that someone struck these pieces after Dickeson’s time can be seen in the large, uniformly machined rim decorations used on the reverse of the same Continental Confederation muling. This rim design is resoundingly different from the hand-engraved rim treatment used on Dickeson’s obverse, with which it was paired. Perhaps after Dickeson’s death, the company that produced his medals sought to profit by quickly preparing new dies from an unfinished Dickeson design; adding a less tedious rim decoration; and combiningthe mismatched sides together to strike new medals on Dickeson’s leftover planchets. It is doubtful that Dickeson would have approved of this sloppy coupling, had he intended to associate himself with it.[ix]

An even stronger indicator that these were post-Dickeson issues is the die emission sequence. These coins were struck after the Dickeson issues and before the Elder ones. It is easy to see that the various post-1876 mulings were struck from an advanced die state. A noticeable obverse die break had developed through the outer circle, just above the C in CONTINENTAL; and die clashing of the sun’s rays appeared through the XII on the sundial, on all post-1876 issues. Additionally, the coiner, whom ever he was, felt it necessary to refinish the die face, filing down and polish the surfaces to remove rust and imperfections, prior to production, creating impressive Prooflike and sometimes DMPL luster on these various mulings.[x]

Some remnants of this die crack (left) and these clash marks (right) are present on all post-1876 issues.

Clearly, the old obverse die was brought back to life by somebody. It was probably after Dickeson’s time, whether it was someone in the 1880s, or even Thomas Elder. It cannot be forgotten that Thomas Elder did have in his possession, at least the obverse die, in 1917, and he did strike some mulings with it, evenusing a reverse that bore his name and date.

But, even if Elder did make those mulings, he did not strike any HK-853s; again, all post-1876 uses of the obverse die, including Elder’s 1917 medal, show the same refinished surfaces, die breaks, and clashing, which are not seen on any known HK-852 through HK-856. We have examined, both in person and through auction records, as many as possible to confirm that none have either the die breaks or the refinished surfaces. In 1980, DeLorey was also of the opinion that “no Elder strikings from the original reverse die are known.”[xi] Anecdotal evidence that they were not reproduced comes in the very low surviving populations of the originals. Of the HK-853, there are about a dozen known.

1917 Thomas Elder Muling. Note that the rim decorations are very similar to the reverse on HK-860. Images courtesy of Heritage Auctions.

With the Elder debate closed, or at least rendered irrelevant to our analysis, the actual restrikes of Dickeson's Dollar came some 85 years after the original 1876 issue, in 1961 and 1962, when the coming Bicentennial created a surge in the popularity ofpatriotic ephemera in America. First, Q. David Bowers’ Empire Coin Company acquired the original Dickeson dies; which were now definitely together and in the famous collection of John J. Ford. Empire then commissioned some 7,200 pieces to be coined in white metal, HK-854A, by John Pinches, Ltd., of England.[xii]

The Bowers Restrike of 1961-1962.click to enlarge.

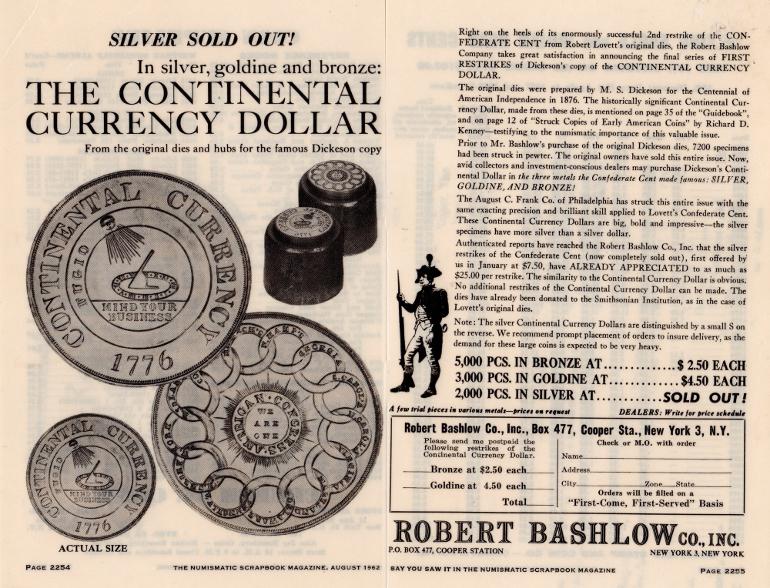

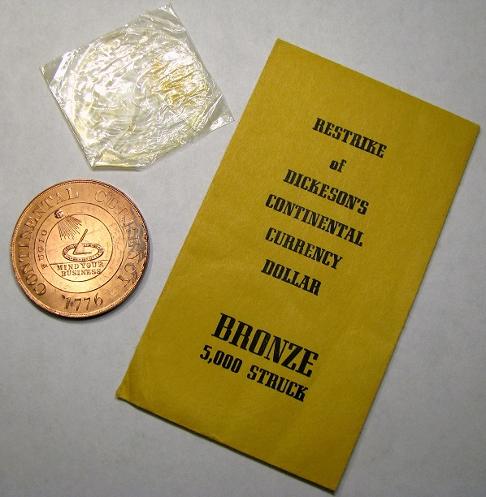

Soon thereafter, the dies were sold to coindealer, Robert Bashlow; already known for coining similar reproductions of the 1861 Confederate Cent. In 1962, he hired a Philadelphia firm, August C. Frank Co., to create a second, massive wave of restrikes of the Dickeson Continental Currency Dollar, amid excessive hype. After 2,000 were struck in silver, HK-852A; another3,000 were struck in golden brass, HK-856A; and another 5,000 in bronze, HK-853A; Bashlow’s advertisements boasted that his medals were already trading for premiums. And further, he claimed that the mintage figures could never increase because “the dies [had] already been donated to the Smithsonian Institution.”[xiii]

And so, with so many variations of the Dickeson Continetal Dollar out there, perhaps it is inevitable that there should be some confusion. Indeed, this set quickly becomes a challenge to assemble due to the number of pieces needed for completion, but also because of the risk of them being misidentified. In fact, some of the modern bronze restrikes have been masquerading as 1876, copper originals. In recent years, we have documented several 1962 Bashlow medals that were accidentally certified as 1876 originals and sold at auction by unwitting dealers, to equally unaware collectors, for huge premiums. If all slabbed and all catalogued examples of HK-853 could be recalled and re-categorized, the true survival rate would be even smaller than population reports indicate. And, while our focus is on the 853, the other compositions have been known to be confused, as well.

The problem stems from a lack of reliable information on the nuances of these medals, and a detailed analysis is therefore in order. Popular belief is that the 1961 Bowers and 1962 Bashlow Restrikes can be differentiated from the 1876 Dickeson originals by the presence or absence of a few reliable die scratches around the word CONTINENTAL. Unfortunately, while this does work for the white metal Bowers Restrike, it does not always work for the bronze pieces by Bashlow.

First, one must accept that, despite misleading assertions made in Bashlow advertising, the die variety analysis confirms that neither the Bowers nor the Bashlow pieces were struck from the original Dickeson dies. Rather, transfer hubs or dies were made from molds of the original dies, before Bashlow donated the original dies to the Smithsonian, where they reside today. Multiple dies mean multiple diagnostics. In fact, if the diagnostics do not match up, how could these medals be from the same dies? They are not.

Note the S near the bottom of the reverse on Bashlow's silver medal, HK-852A. Image courtesy of EZ_E of the NGC forum.

It was long believed that Bowers and Bashlow used the original dies, but in his article, DeLorey confirmed that Bashlow actually made transfer dies, noting that “the transfer hubs are still in numismatic circles, as are at least one copy obverse die and two copy reverse dies.”[xiv] More recently, David Bowers confirmed, in writing, that both his 7,200 white metal restrikes, and Bashlow’s various issues, were made with transfer dies.[xv] An ounce of common sense tells us that Bashlow must have had more than one set of dies because his silver version displayed a special S mark on the reverse, in the fashion of a mint mark, denoting its silver content. It was impossible for that to be struck from the original die.

On the Bowers dies, it's harder to tell because Bowers preserved much of the original die imperfections. It appears that all the Bowers Restrikes were coined from a single set of transfer dies, which display several prominent, unique die defects. The most notable of these is a die gouge in the beading above the O in CONTINENTAL, which holds true as a diagnostic of the Bowers issue. This flaw does not seem to exist on the original dies. Also, the Bowers Restrikes were originally advertised as Proofs, and they do in fact display deeply mirrored PL and even DPL luster, indicating special preparation of new dies. That said, the Bowers dies faithfully reproduce the classic die break near the C in CONTINENTAL, as well as some of the clashing through the XII, all of which, again, developed at some point after the 1876 runs were completed. Evidence of die rust and die scratches were also preserved on the Bowers dies. It is easy to see how some may think these were struck from the original dies. However, because they are struck in white metal, they cannot be confused with the copper HK-853, which is our subject here.

As for the various Bashlow pieces, those of golden brass, which he called “goldine” do not resemble the originals in any way. Further, Bashlow’s silver pieces have their distinctive S mark. Therefore, these two metallic compositions can be eliminated from the discussion of diagnostics. Likewise, Bashlow advertisements suggest that some were struck in various other metals as “trial pieces” or trial strikes.[xvi] While these are not specifically documented, at least one silver Bashlow Restrike has been found to be struck over a Peace dollar; another in gold was struck over a U.S. Double Eagle. These over-strikes are likely what were referenced in the Bashlow ads, and again, do not pose any risk of being misidentified with 1876 originals.

On the other hand, the bronze pieces are more easily confused with the 1876 copper originals, as there are no reliable, published diagnostics. Sometimes the Bashlow packaging even leaves these red bronze medals with dark streaks and, occasionally, brown patina; making them look older than they are. Full red specimens are actually very scarce.

In terms of diagnostics, the die defect above O, used to identify Bowers Restrikes, is absent from Bashlow’s dies. Instead, collectors have been looking for a die scratch at the rim, between the C and O in CONTINENTAL, as the diagnostic of Bashlow pieces. People actually use this to tell whether or not they have an 1876 original. However, this advice has proven inadequate; the die scratch is actually a die crack that developed after a number of coins were struck from aBashlow obverse die. Our analysis of many high-grade pieces reveals some examples with and without the crack. Additionally, we have observed examples showing as many as three cracks along the word CONTINENTAL. There is a better method of identification.

But first, we must address the fact that it also remains possible, though unlikely, that more than one set of dies was used to achieve this high mintage, i.e., 5,000 in bronze and 3,000 in brass, but our analysis was not conclusive. We did find evidence that the same cracked dies were used across both bronze and brass, which could indicate that the surviving obverse and two reverse dies, about which Delorey spoke, were the only dies produced.[xvii] This seems the likely case, as we also noticed extensive die polishing taking place after the dies cracked, which indicates that efforts were made to get extra life out of them by continually refurbishing them along the way. We also determined that the silver piece were, in fact, struck prior to those of brass and bronze, confirming that part of Bashlow's ad to be true.

The same obverse die was used interchangeably on both bronze, HK-853A, and brass, HK-856A, pieces. Early die states of Bashlow's dies show no cracks on right side, and later ones show three or more. Therefore, die lines on the right side are not a reliable diagnostic of Bashlow Restrikes.

The previous information is valuable and interesting, but frankly, unnecessary. There are much easier ways to tell the differences between the 1876 and 1962 issues. The restrikes actually bear little resemblance to the 1876 originals, in the eyes of seasoned experts, or just anyone who has actually seen the real Dickeson medals. First of all, the intricate details and luster flow lines of the hand-engraved, Dickeson originals do not compare to the factory molded appearance and transformed, uniform surface texture of the modern, transfer die restrikes. The appearance and appeal of hand-engraving cannot be replicated by molding.

In addition to completely changed surface finish, the Bashlow issues are actually missing some major details. Bashlow’s transfer dies were heavily polished to remove evidence of the aforementioned die breaks, clashes, and die rust (these features were all preserved on the Bowers issue). DeLorey may have examined the Bashlow hub, firsthand, as he noted that “95% of the die break had been removed” from it.[xviii] Just a tiny spike is all that remains of the die break, on all Bashlow medals.

However, Bashlow did not stop there; the transfer dies were so heavily resurfaced to remove the old-time defects that major design elements were also carelessly erased. Nearly all definition of the table top is missing, in fact. The top left edge is almost gone on silver Bashlow pieces, and completely erased on the later brass and bronze strikes. The sundial seemingly hovers in mid air. Parts of the sun’s delicate rays, as well as much of the fine detail around the rims, are also gone. The shelf-like connectivity of the long, plump beads on Dickeson’s original medals are weakened on silver Bashlow HK-852As, and degraded to small, misshapen, separated nubs on the 853s and 856s that are so far away from the rims that they too, seem to be floating. This effect becomes more pronounced as the Bashlow dies wore out and were continually polished, taking away even more of the beading each time. One will also observe a thin, wire-like rim on the Bashlow bronzes, which stands in sharp contrast to the thick, squared-off rims of the copperHK-853. These skimpy beads and wire rims bare no resemblance to the original medals.

The hand-engraved table lines on Dickeson's original dies, which weaken over time; as seen on Bower's dies; actually disappear by the time Bashlow struck his brass and bronze pieces. Click to enlarge.

1) The thick rims and connected beading of the 1876 dies do not compare to the Bashlow dies. 2) The Bashlow dies show a distinct die defect left of the date. 3) The same dies were used interchangeably across both compositions, suggesting these may have been struck to order. 4) Late die states show misshapen beading.

Additionally, there is an obvious flaw on all Bashlow pieces, which is a probably the best diagnostic. A curved, incuse gouge that interrupts the dentils just left of the date is readily visible on all Bashlow Restrikes, across all metallic compositions. This defect was likely created on the die or hub during the initial transfer process. This flaw is easy to spot and is a true diagnostic of Bashlow’s crude creations.

Finally, in differentiating original from restrike, one should not forget the hefty nature of the 1876 copper medals. Auctioned examples of HK-853 have ranged between 3.75mm and 6mm in thickness. The Bashlows were made on a standard, 2.5mm planchet stock and are much thinner, lighter, and easily discovered imposters. The same is not true of the white metal pieces. Recently, we discovered an original Dickeson Dollar in White Metal, HK-854, struck on a 2mm thick planchet. More information can be found in our original article, but in summation, thickness alone cannot be used to differentiate white metal originals from the 2.5mm Bowers Restrikes.

In summary, only the original 1876 strikes were accomplished with perfect dies. Between 1882 and 1917, the obverse die was put back into service, making mules that showed clashing, die scratches, and heavily polished, refinished surfaces. Next, the Bowers transfers were made in England in 1961 to 1962, closely mirroring the original dies except for an obvious die defect near O and smooth, gleaming, DMPL surfaces. Bashlow’s transfers were made the following year in Philadelphia, from dies that were heavily lapped to remove the original imperfections, along with many parts of the design, including most of the table lines and beading.

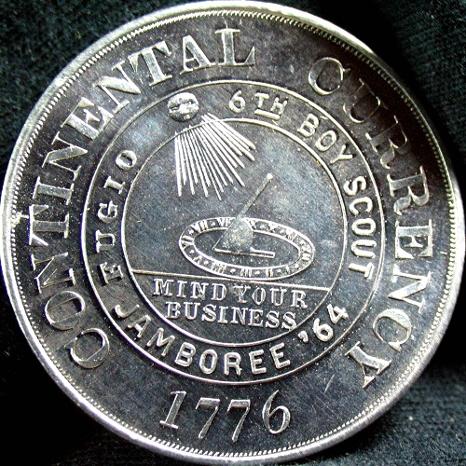

The 1876 Dickeson Continental Currency Dollar Copies are both coveted pieces of numismatic history and high-quality, early So-Called Dollar treasures. Yet, because few people have been able to examine original 1876 copper examples, and because there are so many restrikes, misinformation has caused some modern bronze pieces to be confused with copper originals. High demand for representations of the historic Continental Currency Dollar will continue to drive interest in related So-called dollars. For instance, the Dickeson design was used again in 1964 to create dies for a Boy Scouts medal, differing from the 1962 version only in its added inscription, "6th BOY SCOUT JAMBOREE ’64," on the obverse, and the word "COPY" on the reverse. Indeed, perhaps Bashlow was right that his Continental dollars “were big, bold, and impressive;” the silver version contained “more silver than a silver dollar,” after all.[xix] Nevertheless, if the Bashlow Restrikes are large, hefty, and shiny, when considered by themselves, they are actually cheap imitations of Dickeson’s original medals, especially those struck in copper.

Variety Attribution Guide

Footnotes:

[i] Hibler, Harold E.; Kappen, Charles V. So-Called Dollars: An Illustrated Standard Catalog. Tom Hoffman, Dave Hayes, Jonathan Brecher, John Dean Ed. Clifton, NJ: Coin & Currency Institute. Kindle Edition. 1963, 2008. P 164

[ii] Bowers, Q. David. Whitman Encyclopedia of Colonial and Early American Coins: The Only Authoritative Reference on All Pre-Federal Coinage. Atlanta; Whitman Publishing, LLC. 2009. P 238.

[iii]. Bowers, 305. Of Dickeson’s Manuel, Bowers notes that, “Today it remains a classic and is worthy of rediscovery by collectors” (Bowers, 18).

[iv] Bowers, 307.

[v] Bowers speculated of “additional pieces by Elder” (Bowers, 307).

[vi] DeLorey, Thomas K. “Thomas L. Elder: A Catalogue of His Tokens and Medals.” The Numismatist. Vol. 93, No 6-7. June-July. American Numismatic Association, Colorado Springs. Crawfordsville, Indiana. R.R. Donnelley & Sons Co. (1980). p 1622.

[vii] DeLorey, 1623.

[viii] DeLorey, 1622.

[ix] For what it’s worth, this distinctive rim treatment also appears on a muling of Dickeson’s obverse and Thomas Elder’s dated, 1917 reverse.

[x] DeLorey found that this refinishing was probably done to remove some of the clashing that had developed on the well-used dies (DeLorey, 1623).

[xi] DeLorey, 1624.

[xii] Bowers, 306 .

[xiii] Bashlow, Robert. “The Continental Currency Dollar.” The Numismatic Scrapbook Magazine. August 1962. P 2255

[xiv] DeLorey, 1623.

[xv] Bowers, 307.

[xvi] Bashlow, 2255.

[xvii] A detail that DeLorey also asserted (DeLorey, 1623)

[xviii] DeLorey, 1624.

[xix] Bashlow, 2255.

Bibliography

Hibler, Harold E.; Kappen, Charles V. So-Called Dollars: An Illustrated Standard Catalog. Tom Hoffman, Dave Hayes, Jonathan Brecher, John Dean Ed. Clifton, NJ: Coin & Currency Institute. Kindle Edition. 1963, 2008. P 164.

Bashlow, Robert. “The Continental Currency Dollar.” The Numismatic Scrapbook Magazine. August 1962. P 2254-2255.

Bowers, Q. David. Whitman Encyclopedia of Colonial and Early American Coins: The Only Authoritative Reference on All Pre-Federal Coinage. Atlanta; Whitman Publishing, LLC. 2009.

DeLorey, Thomas K. “Thomas L. Elder: A Catalogue of His Tokens and Medals.” The Numismatist. Vol. 93, No 6-7. June-July. American Numismatic Association, Colorado Springs. Crawfordsville, Indiana. R.R. Donnelley & Sons Co. (1980). p 1337, 1622-1624.

Thomas Elder and HK-860 images used with permission from Heritage Auctions.

Special thanks to EZ_E of the NGC forum for supplying original Bashlow advertisements from The Numismatic Scrapbook, in addition to several photographs.